In the moments after Kenny was born, Kenneth Watkins remembers feeling happier than he had ever been in his life. Blissed out, he couldn’t stop staring at his son — the impossibly tiny toes and fingers, his curly brown hair, his perfect little mouth.

Watkins brought Kenny home from the hospital to his mother’s apartment in the Bronx in March 2017. A few days after they arrived, a pair of caseworkers from the Administration for Children’s Services, New York City’s child-welfare agency, knocked on the door. The caseworkers said they were conducting a routine welfare check on Kenny.

Watkins had no history of violence or mental illness, no criminal record, and was not accused of putting Kenny in danger. He knew, however, that Kenny’s mother, Iris Rohlsen, had a complicated history of abusive relationships. She’d had nine previous children, all of whom either were in foster care or had been adopted.

Watkins invited the social workers inside. He showed them that Kenny was healthy and that he had a crib and diapers and clothes. He remembers saying proudly that Kenny was his first child. The social workers seemed satisfied, but as they left, they asked Watkins to come to their office the following day and to bring Kenny. They said they wanted to talk more about Rohlsen.

The next morning, Watkins, his mother, and Rohlsen brought Kenny to an ACS office in the Bronx. They were ushered into a windowless room, and an ACS worker asked Watkins to hand Kenny to another employee while they talked. Watkins did as he was asked.

A few minutes later, he learned the true purpose of the meeting. Because of Rohlsen’s fraught record, the agency had deemed Kenny to be in imminent danger and was taking immediate custody of him. The removal, as such separations are called, was already in effect. Watkins collapsed on the floor and started screaming and crying — “a perfectly normal thing to do,” his attorney, Yusuf El Ashmawy says, “for someone who has just been told, ‘Your baby is being stolen from you.’ ”

Eventually, Watkins calmed down enough to hear social workers direct him to appear at the family-court building in lower Manhattan, where ACS was filing a neglect petition in the case. He rushed downtown, ready to plead with anyone who would listen to get Kenny back.

At the courthouse, Watkins found himself in a confounding situation. The ACS petition had been filed solely against Rohlsen, who was listed as the respondent, a term that in family court is the equivalent of a defendant. Because Rohlsen was still married to another man, Watkins was not automatically recognized as Kenny’s father. Until he could prove his paternity, he would have no official standing in the case.

Like child-welfare agencies across the country, ACS has enormous and largely unilateral power to separate children from their parents if caseworkers suspect abuse or neglect. Each year, the agency files thousands of neglect petitions in New York City’s family courts; about one in five results in the removal of a child from the parents. Kenny’s case belonged to a subset of removals that occur even before a petition has been filed in court — a scenario meant to apply only when there is “imminent danger to the child’s life or health.”

To get Kenny back, Watkins would have to prove, first, that he was Kenny’s father and, second, that he could provide a safe and stable home for him. Watkins worked a job administered by the city’s welfare system, and he had few resources to mount the kind of legal campaign necessary to regain custody of his child. Still, he was determined to try. The next morning, he returned to the same courthouse in lower Manhattan and filed a petition for paternity. Then he waited.

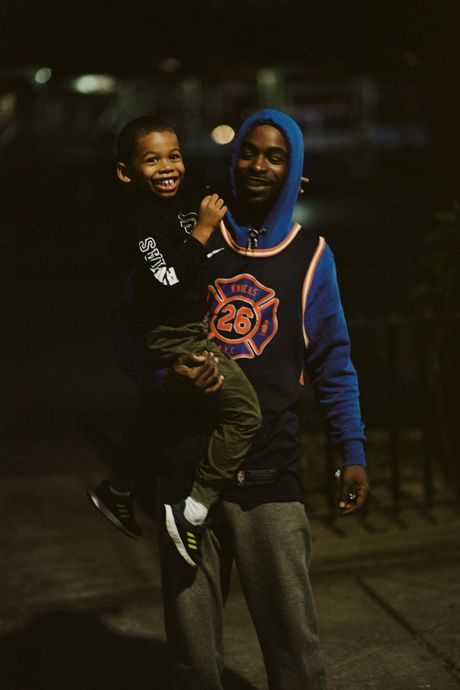

Photo: Khalik Allah

Watkins first met Rohlsen in the spring of 2016. Both worked for the Parks Department in Flushing Meadows doing maintenance — weed whacking, lawn mowing, sweeping. “One morning, we were going out for breakfast before work and Iris had a friend with her. They said they didn’t have enough money to eat, so I bought breakfast,” Watkins says. “Iris hip-bumped me, kind of flirty. Before the day was over, she gave me her number. I gave her a call, and we started messing around from there.”

Two months later, Rohlsen was pregnant. Watkins, who is slight and soft-spoken, described their relationship up to that point as casual — Rohlsen was still dating another man — but he wanted something more serious. “I saw something different in her. She was quiet. I liked how nice she was,” he says. He was happy at the prospect of becoming a father. He felt a kinship with Rohlsen. Both had grown up poor, and both had spent most of their childhoods in foster care.

Watkins, who has two older brothers and three younger half-siblings, has few childhood memories of his father. His mother, Linda Archibald, was loving, but she was sent to prison for drug possession when he was 4 years old. Watkins and his two older brothers were placed in foster care. He and one of his brothers ended up in the home of a woman who had six children of her own. She eventually adopted both of them.

Watkins describes his adoptive mother as kindhearted, but he never stopped missing his biological mother. When he was in his mid-20s and living in Florida, he found Archibald on Myspace and contacted her. He discovered she was out of prison and living in the Bronx. Within a week, he had returned to New York to visit her, and he eventually moved into her apartment in a public-housing project — the apartment where ACS would eventually come calling.

Rohlsen was also placed in a foster home at age 4, after a fire at her family’s apartment got the attention of ACS. (She says her brother accidentally set the fire while trying to kill a spider under her bed.) As a teenager she was caught shoplifting, and she ended up at a girls’ group home, which she described as “like a prison.” By age 15, she was pregnant.

Almost from the beginning, Rohlsen’s life as a mother was wrapped up in the city’s social-services programs. Although she was never accused of directly abusing any of her children, she had on at least one occasion tested positive for cocaine and marijuana, and she had numerous relationships with partners who were violent. Not long before Kenny was born, her then-husband had pulled a gun on her and their two kids and ended up shooting himself.

In cases where ACS finds such a pattern, the agency, under a theory known as derivative neglect, can petition to remove a child without establishing any new abuse or neglect. Shortly after Kenny was taken, ACS filed a motion arguing that given Rohlsen’s history, the court should find that “reasonable efforts” to return the child to his home “shall not be required.” Rohlsen didn’t put up a defense.

The same day that Kenny was taken from Rohlsen and Watkins, he was placed in a foster home. By random assignment, he ended up in the Manhattan home of Tomiko Lyons and Clarence Coaxum, an affluent Black couple. Lyons, a trained social worker with degrees from Columbia and the University of Pittsburgh, helped found the Titus School, a private special-education school in the Financial District. Coaxum also graduated from Columbia and now works at the university as a finance director.

The couple declined to speak with me, but court records praised their care for Kenny. Like all prospective foster parents, Lyons and Coaxum underwent a rigorous approval process. Part of that process includes the very clear instruction that the foster system is meant to provide a temporary home for the child and that reunification with the birth parents, whenever possible, is the goal.

In August 2017, after five months of trying, Watkins was able to convince the court that he was Kenny’s biological father. At that point, there should have been no obstacle to bringing Kenny home. The long-held legal standard in custody cases is the “best interest of the child.” In New York, the state court of appeals has interpreted this to mean, wherever possible, keeping families intact. The role of the biological parent is considered almost unassailable, except in cases of abuse, abandonment, or profound parental misconduct.

But once ACS assumes custody of a child, it can be difficult to persuade the agency to move toward family reunification. “Everyone is trying to cover themselves,” says Philip Katz, a family-court attorney who represented Watkins during the first two years of the case. “At the back of the ACS attorney’s head is always, Am I going to open up the paper and see that Kenny got hurt with Mr. Watkins at the helm and I’m going to be in trouble.”

Watkins and Kenny at 5 months old in August 2017. Photo: Courtesy of Kenneth Watkins

Instead of returning Kenny to his father, the agency kept him with his foster family but allowed Watkins to have weekly supervised visits. Pending further hearings, ACS instructed him to enroll in parenting classes and undergo a battery of psychological evaluations.

“ACS didn’t think it was urgent because he was getting access to his son,” says Katz. Watkins had stumbled into the heart of a dysfunctional system — the slow rolling of the process through inertia both intentional and not. From the outside, Watkins’s difficulties seem extreme, but it is entirely normal for individual cases to take multiple years to resolve.

In December 2017, four months after Watkins had been declared the father, he appeared before a family-court judge (known as a referee) for a so-called permanency hearing. The attorneys for ACS and the Legal Aid Society, which was representing Kenny during the proceedings, both recommended keeping the boy in foster care. They were concerned, they told the referee, that Watkins was still romantically involved with Rohlsen and that he was living at his mother’s apartment, which the attorneys found objectionable because of Archibald’s decades-old drug conviction. The referee deferred to them and pushed the case to the next hearing, which was scheduled for several months later.

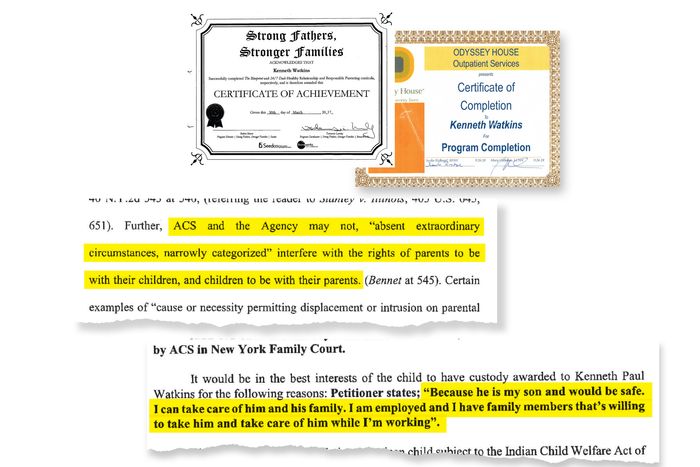

As the case inched forward, Watkins filed a second petition officially declaring his intention to seek permanent custody of Kenny — the first had somehow been lost. In the section where he is asked to explain why the court should allow him to take custody of Kenny, Watkins wrote, “Because he is my son and would be safe. I can take care of him and his family. I am employed and I have family members that’s willing to take him and take care of him while I’m working.” By this time, Kenny was 17 months old.

Watkins never spoke ill of Kenny’s foster parents to me, but he says he felt keenly the class differences between his son’s foster home and the one he shared with Archibald. He described an occasion when he’d bought Kenny a pair of Nike sneakers, but the next time he saw Kenny, he wasn’t wearing them. Lyons told him Kenny had lost them, but Watkins wasn’t so sure. “I got the feeling they just didn’t like my taste.”

As months turned into years, Kenny grew from a baby into an exuberant toddler with a broad toothy smile and deep dimples. He had his father’s long curled eyelashes. And yet, again and again, Kenny’s return was delayed — until after Watkins took one more parenting class, one more drug test, one more evaluation.

Watkins became depressed. During one of his mandated therapy sessions, over a year after Kenny’s removal, his psychologist noted, “All he wants is to be a father to his son. Does not remember having depressed symptoms prior to this event. Described himself as happy before losing his son.”

Still, Watkins never missed one of his weekly visits. A “visitation coach” was hired by the foster-care agency to facilitate and monitor him during these sessions, which were documented in detail. Watkins understood he was being scrutinized and that his future with his son hung in the balance. One report, more than two years into the case, still lists Watkins as the “alleged father” and notes he is required to do yet another parenting class, as “there remain concerns about his parenting skills.”

During this period, Rohlsen also had visitation rights, but she frequently skipped her dates. An agency report noted the coach was “working with Ms. Rohlsen to help her engage in age-appropriate play and with both parents regarding being more proactive with Kenneth’s physical care, such as when to change his diaper and when to wipe his nose.”

The contrast with the reports about Lyons and Coaxum’s household were stark. The foster parents were praised because they could “ensure that all of Kenneth’s needs are met and provide him a positive environment to socially interact with children his age.” After Kenny had been with the couple for a year, they had a child of their own, a girl, whom Kenny called Sissy. He eventually started going to a day care near Columbia and took swimming lessons at a pool near the family’s apartment.

Watkins believed Lyons and Coaxum were good to Kenny and that they had grown to love him. But all the irreplaceable moments of Kenny’s first years of life — the boy’s first laugh, his first words, his first steps — were happening without him.

The City vs. Kennesh Watkins: Top: A 2019 report calls Watkins the “alleged father” two years after he proved his paternity with a DNA test. Middle: The city noted repeatedly that the foster parents were willing to adopt. Bottom: The original removal did not require a court order.

Top: Watkins was required to attend parenting classes and drug-treatment programs to see his son. Middle: Watkins’s lawyer filed an “extraordinary circumstances” motion to compel the authorities to explain why Watkins could not have custody. Bottom: In his petition for custody, Watkins explained why he should be reunited with Kenny.

In the spring of 2019, a new referee, Pamela Scheininger, took over the case after the original referee retired. By that point, Watkins and Katz had missed several court appearances, which Katz says was owing to a bureaucratic mix-up — he hadn’t been notified of the court dates. When Katz failed to appear at a hearing that May, Scheininger asked El Ashmawy, who was one of the family-court attorneys on call that day, to take over the case.

El Ashmawy is a barrel-chested former petty officer in the Navy who started out as a prosecutor for ACS, but after two years, he switched to defense work. “On any given day, the outcome of a matter would vary wildly depending on which judge is hearing a case or which social worker is filing a petition,” he says. “The arbitrariness, and people’s personalities and how they shape the outcomes, was to me intolerable.” He started his own firm, where he leads the criminal-defense and family-defense divisions, and regularly takes on family-court cases for poor clients, paid from public funds.

Looking over Watkins’s file, El Ashmawy couldn’t understand why Watkins still didn’t have custody. “He did everything that was asked of him,” he says, “and they still wouldn’t give him his son back.”

The day El Ashmawy was assigned the case, he returned to his office and drafted a motion demanding an “extraordinary circumstances” hearing. It was a kind of legal maneuver of last resort, akin to the habeas corpus petitions that Guantánamo Bay defense attorneys filed to access evidence against clients accused of terrorism. The hearing was meant to force the child-protection and foster-care agencies to produce evidence that would explain why they wouldn’t return Kenny to his father.

El Ashmawy believed the child-protection and foster-care agencies had secretly decided that Kenny would be better off staying with Coaxum and Lyons. “Maybe this kid hit the lottery, and the court should say, ‘You’re a nice man, Mr. Watkins, but we’ve decided that you’re less fit to take care of your son than this foster family that is rich and can offer him a good life, so we believe he should stay with them,’ ” says El Ashmawy. “But when you take it to the logical extreme following that line, that seems very frightening. You’re picking and choosing who can be a parent.”

The extraordinary-circumstances hearings unfolded in a series of two-hour sessions over the course of several months. On one side of the courtroom sat Watkins and El Ashmawy. At a long table on the other side were lawyers from ACS, Legal Aid, and Children’s Aid Society, the private foster-care agency that had facilitated Kenny’s placement. These were the attorneys who sought to prove that Watkins, who had been given the opportunity to be a father to Kenny for less than a week, was unfit to be a parent.

Most of the hearing revolved around Watkins’s visits with Kenny, which had been ramping up in recent months. He had even been granted a few overnight visits without supervision.

Catherine Connelly, a director at Children’s Aid Society, testified that on more than one occasion, Watkins had returned Kenny to the agency with a “noticeably wet diaper.” His choice in activities was also questioned, specifically the time he took Kenny to a screening of The Lion King, which Connelly said was inappropriate for such a young child. On another visit, Watkins’s first solo overnight with Kenny, Watkins had returned what Connelly believed was too much change from the meal money he had been vouchered by the agency. Watkins had told the agency he had purchased pizza for Kenny’s dinner and eggs and toast for breakfast.

“Do you have concerns Kenny was not fed enough?” asked Lindsey Lamonica, an attorney for ACS.

“Yes,” said Connelly.

In his own testimony, Watkins was unapologetic. He was confronted with positive drug tests for marijuana, which he said he used to “self-medicate” after Kenny was taken from him. He was questioned about a diagnosis of depression he received from a psychiatrist who had evaluated him. “I was depressed from my child being missing,” he said matter-of-factly.

“What is your response to the agency’s concern that you have fed Kenny inappropriate food, specifically french fries, during a day visit?” asked Jessica Thomas, the lawyer for Legal Aid.

“That’s not the only food I fed him,” said Watkins, his voice defensive. He twisted his baseball cap in his hands, finally adding, “And I don’t believe french fries are a problem because french fries are the same as mashed potatoes.”

During one hearing, Thomas pulled out an enlarged screenshot of Watkins’s Facebook page, which had a photo of Kenny and some friends at a Chuck E. Cheese. In the background, Rohlsen was clearly visible, a violation of the court’s order that she not be present at any of Watkins’s unsupervised visits with Kenny. Thomas moved that Watkins’s overnight visits be terminated.

Scheininger was not pleased and told Watkins to keep Rohlsen away from Kenny. “I’m ordering you not to allow her to have any access to this child during the visit, period,” she said. “If you violate that order, you’re not going to have an issue of continued visitation; you will have an issue of whether you are in contempt of court.”

When he saw the images, Watkins looked ready to burst into tears. He stood up as if to leave the courtroom.

For a moment, it appeared Watkins was about to be once again relegated to the endless path of parenting classes and supervised visits. But when it was his turn to question Watkins, El Ashmawy returned the focus to what he saw as the heart of the matter.

“Did you ever intentionally abandon your son?” he asked.

“No,” said Watkins.

“Did you ever intentionally forgo your parental rights?”

“No,” said Watkins.

“Have you been in agreement of him being away from you?”

“No,” said Watkins.

“Have you told them you want him back consistently?”

“Yes,” said Watkins.

A few minutes later, Scheininger ordered all parties to “settle the case as soon as possible.” Provided that Watkins could follow through with his plan to leave his mother’s apartment, it seemed that Kenny would finally be returned to him. This time, his tears flowed freely.

After the hearing, Thomas sent El Ashmawy a conciliatory email. Although she had been the most forceful of the attorneys in fighting to keep Kenny from Watkins, she now professed that she was somehow unaware Watkins had already been in Kenny’s life when he was taken. “Prior to yesterday, I didn’t know that Kenneth was also removed from your client,” she wrote. “That’s truly awful, and obviously illegal, and I’m hoping we can get to a point where Kenneth can be returned to him as soon as possible.”

El Ashmawy told me that, in a decade of defending clients in child-custody cases, he had represented countless mothers and fathers who had given in to frustration and despair and lost their temper in court or teed off on a social worker. The result was only further restrictions on visitations and longer separations. Watkins was different. “It’s very rare you can find a person who can endure all this,” El Ashmawy says. What he saw as one of Watkins’s defining traits, his passivity, was in this instance an asset. “I’ve seen so many men just give up and walk away,” he says. “Some other guy who was perfectly capable as a father would have been like, Fuck this shit, I give up.”

Photo: Khalik Allah

In December 2019, I met Watkins at his mother’s apartment in the Bronx. A sticker on the door read NEW GRANDPARENT. Watkins told me Archibald had placed it there nearly three years earlier, when Kenny was born.

As he had promised the court, Watkins was not going to be living with Archibald any longer. He could not afford an apartment of his own, so he’d packed a backpack and a suitcase of his belongings. His plan was to pick up Kenny at the Children’s Aid Society in Harlem and go straight to an intake center for the city’s shelter system.

In Harlem, just as Watkins approached the building’s entrance, Kenny rounded the corner with Lyons. He was holding her hand and trailing a rolling suitcase behind him that contained his clothes and his favorite toys. When he saw Watkins, the boy broke into a run and jumped into his father’s arms for a hug.

Inside, as they waited to sign paperwork, Lyons showed Watkins books and clothes she’d packed for Kenny and mentioned that he liked listening to the songs of Raffi. She showed him where his favorite blankie was stashed in the suitcase.

Lyons had brought along a book she and Coaxum had made called Kenneth Is Loved, which included images of his nearly three years with them: Kenny playing with Sissy, swimming at the pool, and on family vacations. As Watkins looked on awkwardly, Kenny sat in Lyons’s lap, happily entertaining himself with the book. He called Lyons “Mommy.”

When Kenny was called for a final physical examination, it was Lyons who took him. Watkins stayed in the waiting room with a social worker, Bettina Thomsen, who was going to accompany him to the shelter-intake center.

Then it was time to say good-bye. As she hugged Kenny, Lyons began to cry and, without another word, abruptly left the building.

“Where is Mommy going?” asked Kenny. There was a long silence, then one of the caseworkers spoke up. “You’re with Daddy now,” he said.

At the shelter-intake center, Kenny held tightly to Watkins’s hand and his rolling bag. They were led to a security checkpoint, where their bags were inspected, then directed to wait by a bank of windows until their case could be processed. Several hours later, after dark, they took a cab to a shelter in the Bronx. As they drove out of sight, Kenny, still holding Watkins’s hand, turned and gave us a wave.

Thomsen acknowledged that as hard as it was to for her to see Kenny enter a shelter, she believed it was what was best for him.

“Maybe when I was newer at this job, I would have made the same mistake,” she said. “You see the shiny house, the nice family, you think maybe it’s better,” she said. “But then these kids get older and so often you see them searching for meaning and belonging and then they are getting in trouble and arrested. They want to know their parents, and they’re asking, ‘Why didn’t you fight for me?’ ”

During his first weeks with his son, Watkins hardly knew what to do with his newfound parental freedom. He didn’t want to let Kenny out of his sight, so he stuck to his routines. He had been working as a health-care aide for his mother, which he now did with Kenny by his side (this was allowed so long as they didn’t live with her). He planned to sign him up at a day care near her apartment.

In March 2020, just after Kenny celebrated his 3rd birthday, the pandemic hit. Watkins decided to leave the shelter system and move to Archibald’s apartment in the Bronx. Although ACS for years had cited the fact that Watkins lived with his mother as a major obstacle to his getting Kenny back, the agency now approved the living arrangement.

I visited Watkins several months after their return to the apartment. Kenny played with Matchbox cars, stopping to chase the family cat or watch cartoons on the big-screen TV. Watkins said Lyons and Coaxum were still in contact with him and planned to have regular visits with Kenny. When I asked how he felt about that, he shrugged. He considered them pragmatically as a resource for his son.

He was more circumspect when discussing Rohlsen. Although she had been at the center of the case that had caused Kenny to be removed, she had been largely absent during the proceedings. There was a seat reserved for her in the courtroom next to Watkins, but most sessions her chair was empty. One day, I saw her slide into the bench in the back row of the courtroom, still in medical scrubs from her job as a home health-care aide.

The evaluators at ACS had written her off as an irretrievably defective parent, but Watkins didn’t see her that way, though he was careful to emphasize that she was never alone with Kenny. They were still friendly but no longer romantically involved.

Over time, Watkins and Kenny settled into their routines, sticking close to his mother’s apartment, playing on the nearby playgrounds. On many weekends, Lyons and Coaxum would drive to the Bronx and pick Kenny up and take him to a restaurant or a park, and eventually Watkins allowed Kenny to sleep over at their home on occasion. He had by now gained confidence in himself as a father and no longer feared that Kenny could be taken from him at any instant. He had also made peace with the fact that however wrong the situation was that had led Kenny to his foster family, they loved him.

He was now dealing with the everyday concerns of a single parent. He was still working as a health-care aide, and there was never enough money. On more than one occasion, he had to visit a food pantry. When the day care told him that Kenny might need specialized schooling, Watkins made sure to arrange it. “It hurt me to hear that about him,” said Watkins, “but I know it’s what’s best for him.”

Late last summer, I met with Watkins, Rohlsen, and Kenny in the Bronx. In person, Rohlsen was very different from the woman who had been written up in the court records and the ACS reports. Bubbly and loquacious, with high, wide cheekbones and the same sly, mischievous humor as Kenny, she was full of ambition and ideas. She said she was trying to get her GED.

She handed me a file folder containing details of her most recent custody case, involving a daughter, Elsa, whom she had given birth to in December 2020. As with Kenny, her daughter had been removed from her custody right away, but this time she was fighting to get her back. “I want to finally be a parent to one of my kids, so I can see them grow up, go to college,” she said. For now, Elsa was with a foster mother. Rohlsen said the woman had already indicated she was interested in adopting her.

After picking up a lunch of Caribbean food from a local restaurant, Watkins, Rohlsen, and Kenny sat down at a picnic table in a sunny park. Watkins dug into the meal and let Rohlsen do the talking. Kenny picked at a few bites before being happily lured away to the playground.

Later, I asked Watkins whether it was difficult to keep Rohlsen involved in Kenny’s life. He insisted that it was worth it. “She’ll always be Kenny’s mother,” he said. “I would never deprive him of that.”